The application of Arnold van Gennep’s rites of passage idea to edge work in process oriented psychology.

There are two main justifications for anthropology. First is the imperative to make a full record of human society. (…)

Second, anthropology feeds the ambition to understand ourselves better by making comparisons with the rest of human kind.— Mary Douglas

Introduction

The edge is a central notion in process oriented psychology. Structurally, the edge denotes the boundary between the primary and secondary processes, establishes the identity framework, and segregates the known from the unknown. As a result, the edge is considered to be the most energetic point of the therapeutic work; therefore, the edge denotes an area of struggle between the new and the old, between the defence of known and safe behaviours along with lifestyles and the attraction of a change. Process work makes an attempt to create a unity by integrating primary and secondary processes; thus, the work with the edge is its most substantial part. There are four sorts of edges in psychotherapeutic work, they vary depending on the patient’s self-development phase. Every bigger edge places the patient in an inconceivable situation, where on the one hand, the individual tends to maintain the status quo, holds a grudge against leaving the safe, familiar niche, and raises fear for unknown and unfamiliar reality. However, on the other hand, the individual has the tendency to develop and widen one’s area of psychological functioning. Additionally, the person senses that as long as they live in such a condition, nothing interesting is going to happen, and without providing the increasing flow of freshness, one is not able to overcome life’s difficulties. Each edge has its sentinels, these are the belief systems whose task is to deter at all costs the individual from reaching to the new territory. The more rigid the identity or the primary process is, the bigger the edge and more fearful its sentinels are (Teodorczyk, 2012). Human psychological development is not possible unless the edge is confronted, therefore, the process oriented psychology has developed numerous methods, which aim to enable the individual not only to embrace the edge, but also cross it. (Diamond; Spark Jones 2012)

The article outlines the rites of passage conception outlined by Arnold van Gennep, then it proceeds to present how the cultural anthropology changes the perspective on psychological work with the edge so as to make it more natural and increase its effectiveness at the same time.

The rites of passage concept developed by Arnold van Gennep.

In 1909 a French etnographer Arnold van Gennep published his work The Rites of Passage, in which he laid out a widely established three-phase approach to the subject of the change. It is amazing that the thirty-something-year-old scholar formulated the idea, which seems to be so obvious these days. What appears to be even stranger is how the preceding cultural anthropology had dealt with an understanding of the change without the knowledge Arnold van Gennep spread.

Every society consists of smaller communities, in which individuals relocate throughout their lives. It applies to manifold divides, it can be liken to a multilayer structure with its different layers. The change applies to every aspect of the human life beginning with the social status in terms of the age, occupation, marital status, motherhood, fatherhood as well as numerous other dimensions; it might be associated with the transition from the profane to the sacred, as well as the physical relocation of individuals to different places.

Since each change is always a way into more or less unknown area of experience it stokes the fear; for this reason, it also confronts the individual with various, but mostly complex and difficult emotions. The fear should be handled or else it can destabilize the individual and the society thereupon.

In ancient cultures, the relationship between the individual and the society used to be more closely-knit than it is presently, therefore the issue was particularly crucial. The societies knew it well and sensed the potential danger of constant movement of the individuals between smaller communities; hence they developed repetitive rules and rituals not only to symbolically comment upon the change, but also to avoid significant difficulties in the entire system. They also framed the society and gave the individual the sense of security. As a result, a stable, repeatable, and identical in its basic structure cycle of the rites came into being. It was supposed to enable rich, deep and safe experience of the change to the community member. One should bear in mind that in many cultures the edge belongs to the realm of the sacred, therefore one must show due respect and care so as to cross it.

The three-phase structure of change based on the rites of passage is as it follows:

- Pre-liminal rites, the rites of separation relate to the withdrawal of the individual from their current status, they detach the person from who they were prior to the change.

- Liminal or transliminal rites are applied to the transitional stage, when the individual is in-between for they have left their status but have not entered the new yet, it is a status-less phase.

- Post-liminal rites, the rites of incorporation of the individual to the new group and attaining the new status.

To give some examples of such three-phase rites, one may consider the period when the boy changes into a man. Obviously, the rites vary according to the culture, however, the stage usually begins with pre-liminal rites such as leaving the women rooms where the boy dwells, the ritual weeping of the women, farewell, hair cut, to mention just a few. The rite guides the young through the transitional period when he is preparing for the initiation trials accompanied by various rituals. After a successful initiation post-liminal rites take place. They introduce the boy to the men’s world and are followed by room changes, feasts, and gifts to emphasize the new period.

Another example includes funeral rites of the Dogon people in Mali. The body of the deceased is taken out shortly after the death. It is transported to a special grotto in the mountains; the rites of separation are furthermore associated with destroying the possessions the deceased used to practice the profession. When a French anthropologist Marcel Griaule, who is known for his studies of the Dogon people, passed away in France, his pencils were ritually broken by them.

The next stage involves the transliminal rites related mainly to the dwelling of the deceased. For the Dogon believe in reincarnation, they perform a ritual tribal dance a year after the death by the means of which the deceased enters the family; after three years, the entire community perform a grand dance so as to reincorporate the deceased as one of its members.

The rites of passage between the sacred and the profane are universally known and appear to be straightforward. Taking the shoes or the caps off is a pre-liminal rite which separates the worshipper from the profane. It might be also accompanied by such rites as ablution e.g. the washing of the feet. However, transliminal rites take place on the way to the temple. They may regard the door or just the threshold. The latter cannot be trodden on, but one ought to kiss it, make a sign, shed the blood or anoint with oil. Subsequently, the rites of incorporation relate to the entrance to the holy place, therefore one ought to kneel, cross oneself or make another symbolic gesture.

To give one more example, the sequence of the pregnancy and childbirth rites among Indian Todas include parting one’s community along with the profession so as to reside in a separate hut. The woman prays to the goddesses and performs special transliminal rites there such as burning hands in two places until birthing. Then, she ultimately returns to the community by the rite of drinking sacred milk preceded by ceremonies protecting against keirt, the evil spirit. (Gennep, 2006, p. 65)

As far as the childbirth rites among the Australian peoples are considered, the tribes entrust children after the birth to a different woman, they also cut the boy’s umbilical cord with a knife and girl’s with a spindle (rites of separation). The child becomes a complete individual after twelve days of which the father spends six days at his friend’s hut and the following six days in his (transliminal rites). Eventually, the incorporation rites are performed so that the child becomes the family and community member e.g. naming or first tooth.

As presented, there are numerous examples of rites, nevertheless the three-phase sequence remains identical.

The application of van Gennep’s model to edge work.

Cultural anthropology perceives the society as a whole comprising smaller communities, likewise, process work recognizes the human psyche as a whole made up of smaller partes known as dreamfigures. The model of thinking based on the multi-dimensionality of various transitions within the community is mirrored by a interpsychological movement between various dreamfigures and the aspects of one’s psyche. As known, working with the edge is the most difficult part of the therapeutic activities; the man is helpless and fearful at the edge, courage and curiosity about the new blend with the desire for an escape and defending the status quo. According to A. Maslow, two core tendencies battle with one another in men’s psyche; they are the defence of the now and the desire for development. However, when it comes to the situation of the modern man it is significantly different from the past, the community support has weakened whereas the individualistic tendencies of the west make the human think that it is he who has to cope with anything. There is also a lack of a framework that can give the structure to the change of the rites so as to make them more straightforward, secure and predictable. There are the vestigial remains of the rites of passage, which are deeply rooted in the human psyche, thus it is not simple to extricate them. Nevertheless, the majority of people are unconscious of their application, hence their impact is limited. Whoever ponders about putting the engagement ring on as a pre-liminal rite which detaches the maid from her status and introduces to the transition ending up with a post-liminal rite that is putting the wedding ring on? To give another example, who considers the school ball traditionally held 100 days before the final exams as a separation rite where they are detached from their current status and introduced to the transition period as a result of which the graduates become mature and have a school graduation ball as an introduction to the world of adults?

Regardless of these abortifacient ritual forms, each individual more or less unconsciously develops their own rituals so as to aid them while undergoing the change, these are purchasing goods, different kind of divinations showing the ,,right” sequence of dealing with a change or doing specific activities, to mention just a few. In such a context, it becomes clear that one must also find some kind of psychopomp, a guide that helps to escort the individual to the new land. The person’s therapist may become such a figure in the best case scenario or a cult master in the worst scenario. Therefore, the therapy development seems to be a function to depart from the structures to fully and safely undergo the change. The therapist, regardless of how successfully performs their job is not capable to give the individual what the social rites of passage would.

However, anthropological thinking can deepen our understanding of the process of change and expand the variety of therapeutic work with the rough time in somebody’s life. This applies especially to substantial changes as well as such situations when the individual lacks a personal pattern of confronting and implementing the change. Jung deemed that archetypal dreams may appear in similar circumstances. The dreams are supposed to indicate the universal pattern of the change, alas, they do not always occur. Besides, the experience of the individual with the dreams may result in the man’s utter helplessness.

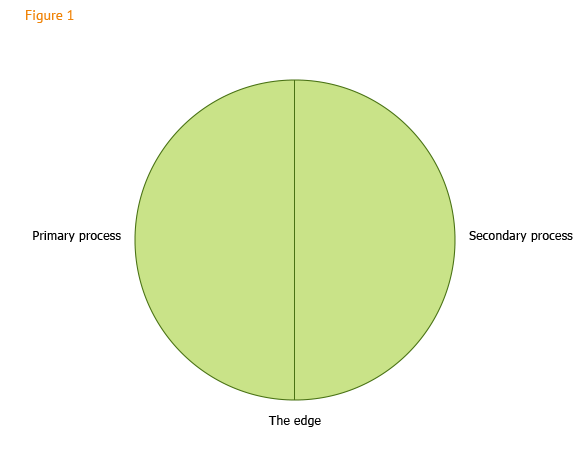

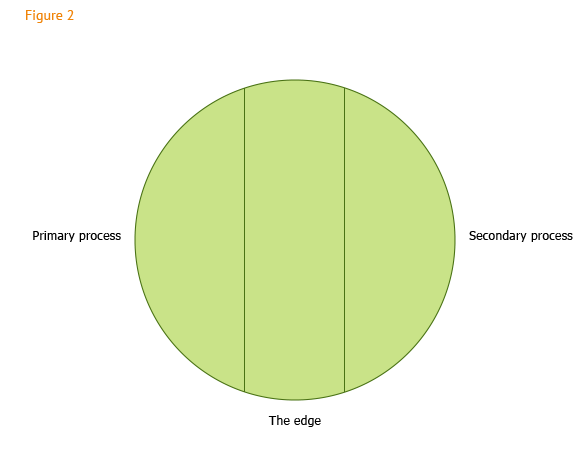

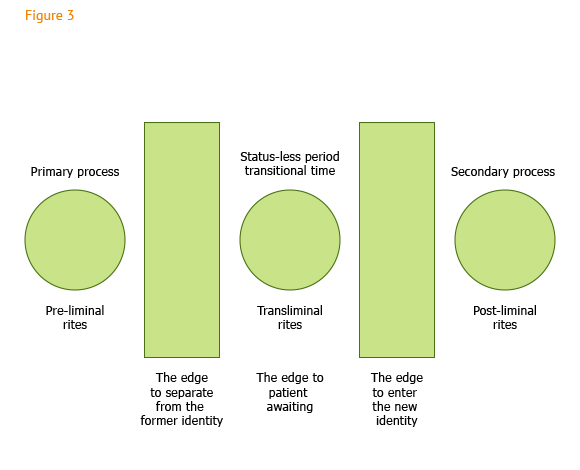

Our thinking of dealing with the edge should be altered. First of all, under no circumstances is the edge the boundary line between the primary and the secondary processes, it is not even the frontier area or a zone of no one’s land in-between (figure 1.2). The approach is a considerable simplification since it does not provide for the natural dynamics of the approach to change, deeply rooted in the human psyche, which the ancient communities knew well.

The edge in its new meaning would play a role of a necessary transitional time and a need for experiencing it in completely new mental circumstances. The individual must firstly experience the stages of separation from their world with all its consequences so that they can enter into some kind of bardo state, the state of transition and status-less period. In the meantime, the person is no longer what they used to be, what is more, they are in-between, neither do they belong to the former identity nor to the prospective one. That is the time of reflection and preparation for the next stage. The phase proves incredibly difficult, the sense of ignorance and the tendency for the quickest and simplest solution dominate; however, such solutions are only temporary and shallow. Time and patience are the cornerstones at this stage, but the vital support comes from the consciousness of being in the very phase. Moreover, it is also the stage of recovery. Although it seems to be a standstill and fairly difficult moment after passing the first part of the edge (the separation from the former identity), the respite is brought. Nevertheless, it is also the period when the individual acquires the robustness so as to face the next part of the edge and gain the entrance to secondary processes allowing the person for the change of the identity. Due to the fact that the human is no longer what they used to be while transition, they can derive support from allies, which the individual would not have thought of if they had been in their older identity’s shoes. The detachment from the old identity allows the individual to confront various aspects of reality, not necessarily those directly connected to the process of change. The human is strengthened by doing different activities, they foster the sense of robustness and agency. After having achieved the proper level, the individual can attempt the next stage of the edge – to enter and develop a new identity.

Such thinking divides the process of confronting the edge into three separate processes. The edge to separate from the former identity differs enormously from the edge to stay in the time of transition, in which one being in-between patiently awaits, and this stage is also dissimilar to the edge to enter the new identity. Each of these aforementioned edges is in a way an area that can be divided into micro-edges or micro-stages of the transition; they are determined by the kind of dance on the edge, the edge figures, strength as well as the attraction of the secondary process on the other side.

Source: own elaboration.

This framework for thinking creates more space and gives the individual more room for being in-between, indeed, it indicates the necessity to separate the zone as an essential constituent of the process of change. It changes binary thinking into more process oriented model, reduces the strain on the change rapidity, as well as attributes its formula and framework. Unless the aforementioned factors are taken into consideration, one is likely to give themselves to the common desire of human. What is hereby meant is the need to have everything done efficiently, quickly, and effortlessly. It is also equivalent to the New Age way of unrealistic thinking. As a result, the individual seeks a simple, will-oriented and unlimited psychological development. To conclude, I should now mention a classic story from the zen school about a man who wanted to learn sword-wielding.

The man tracked his master down, betook himself to him and asked, ‘Master, I’ve come to you for I want to learn sword-wielding. I am highly motivated and strong-willed, how long will it take?

The master glanced at the man and answered, ‘Well, looking at you, I’d say ten years the fewest’

‘Ten years!’ exclaimed the man, ‘That’s incredibly long! What if I practised more persistently, strenuously, if I learnt all day and night long, how much time would I need then?’

After a moment, the master replied, ’20 years.’

APPENDIX

The Rites of Passage Ceremonies – Exercise

1. Think of an important edge you have been working with recently.

I. THE RITE OF SEPARATION

- Define your identity, the primary process you are currently in which does not enable you to cross the very edge.

- Determine what exactly the stage and area of the identity is like.

- Draw on a piece of paper a few important symbols denoting the world, alternatively, other signs representing the constituents of the identity.

- Sit on the very piece of paper, try to feel the world, its vibrations, energy, everything it gives you, still, attempt to embrace what it hinders you from.

- Think of a ritual (gesture, movement, dance, song, behaviour, returning an item, the body posture etc.) which symbolizes your separating from the area. Do your best so as to use the ritual to represent the energy and the essence of the reality.

- Do it now.

II. TRANSLIMINAL RITES

- Neither you belong to the former nor to the latter identity. Try to feel in-between. Endavour to experience what it is to be at the transistion stage like. Do not rush, take your time to embrace your ,, I-do-not-know condition”. What activivities can you perform so as to strengthen your power and agency within this period? Devise the plan.

- Try to express your thoughts and feelings by the means of a few important symbols, or other signs denoting vital constituents of the stage. Draw them on a separate piece of paper.

- What rite (gesture, movement, dance, song etc.) best reflects the period of the transition process? Do it now.

III. RITES OF INCORPORATION

- Think now of the reality on the other side of the edge. What is it like? What are its main constituents? What world could it represent? Draw on the third piece of paper, a few important symbols denoting the very reality, alternatively, other signs reflecting its significant elements.

- Stand in front of the sheet, feel the entrance condition and imagine what rite to gain the entrance to the new territory you would need. Do your best so that the rite reflects the energy and the essence of the new area. Additionally, appreciate the importance and weight of the edge which inhibits you to gain the access to the territory in a normal life. How can you express it?

- Carry the rite out and enter the new territory. Sit on the sheet and feel what it is like to be in a completely new place. Appreciate the route you have come to be here.

- Plan to conduct everything you have devised in the near future in the consensus reality.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Diamond, J., and Spark Jones, L. A Path Made by Walking. Process Work in Practice. Portland, Oregon: Lao Tse Press, 2004.

Douglas, M. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of The Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966.

Douglas, M. Implicit Meanings. Selected Essays in Anthropology. London and New York: Routledge, 1999.

Gennep A.van. The Rites of Passage. London: Routlegde and Kegan Paul, 1960.

Teodorczyk, T. “Psychologia zorientowana na proces – teoria i praktyka.” Nauka Polska XXI. 2012: p. 223-247.

Turner,V. The Ritual Process. Structure and Anti structure. New Jersay: Transaction Publishers,1969.